Biodiversity of Cayuga Lake

The Cayuga Lake Basin is home to a great diversity of plants and animals, many of which are native and some of which are not:

Vascular plants (ferns, conifers, angiosperms, etc.): 1,265 native species, 777 non-native species

Non-vascular plants (mosses and liverworts): 48 species

Fungi: 26 species

Earthworms: 20 species

Insects: ~10,000 species

Land snails: 56 native species

Amphibians (frogs, toads, and salamanders): 16 native species

Reptiles (snakes): ~20 native species

Breeding birds: 150 breeding species

Mammals: 55 native species

If you want to learn more about the fauna and flora of the Cayuga Basin, we recommend our “Field Guide to the Cayuga Lake Region: Its Flora, Fauna, and Geology” by James Dake (2018). It may be purchased from our online store.

Cayuga Lake is home to at least 90 species of fish, at least nine of which were introduced by humans over the past two centuries. Other residents of the Cayuga Lake include 8-10 species of mussels, at least 25 species of crustaceans, and 43 species of aquatic plants. Some of the native and introduced (non-native) species that occupy Cayuga Lake are introduced below.

Native Species in Cayuga Lake

Fish

Salmon and Trout (Overview)

Introduction

Fishes referred to as “trout” and “salmon” are all related, and all belong to the family Salmonidae, but common names can be misleading about which species is more closely related to which. Five species of salmonids occur today in the lakes and streams of central New York State, including the Finger Lakes, but only three are native to the region. The other two have been introduced intentionally by humans as sport and food fishes.

Evolution

Large salmonids in New York are assigned to three genera: Salvelinus (char; Brook and Lake Trout), Salmo (Atlantic Salmon and Brown Trout), and Oncorhynchus (Rainbow Trout). The evolutionary relationships among these three genera are shown in the diagram below. The co-occurrence of species in New York is a result of both natural and human history. Brook Trout, Lake Trout, and Atlantic Salmon were native here. Rainbow Trout are native to the Pacific Coast of North America, and Brown Trout are native to western Europe; both were introduced to eastern North America (and elsewhere) in the nineteenth century for sport fishing.

Phylogeny (evolutionary tree) of Salmonidae.

Ecology

Salmonids are predators, and large salmonids such as trout and salmon are usually the top (“apex”) fish predators in their local environments. They are opportunists, and will feed on whatever is available at the time. In freshwater, salmonids are heavily dependent on the larvae of aquatic insects such as mayflies, caddis flies, and stoneflies. This is the reason that “fly fishermen” design their lures as they do. The amount of food a fish must consume depends on the temperature of the water; metabolism increases in warm water and so more food is required.

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar)

Atlantic salmon. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Landlocked Atlantic Salmon belong to the same species as oceanic Atlantic Salmon. They occur on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, on the west side from Greenland to the Connecticut River. Cayuga Lake’s salmon rarely reach sizes greater than 36 inches long and 30 pounds, but the species can reach 100 pounds and more than 60 inches.

Atlantic Salmon were originally native to the Finger Lakes, but overfishing and environmental changes drove them extinct here in the early 19th century. Today, they are regularly stocked in Cayuga Lake, but they do not breed successfully. This is because an introduced fish, Alewife (see below), their favored prey, contain an enzyme that interferes with their reproductive success. This situation has been called “Cayuga Syndrome.”

The Adirondack Fish Hatchery in Saranac Lake raises Cayuga Lake’s stocked salmon. For many years, these fish were from a strain derived from Little Clear Lake in the Adirondacks, but they are now derived from fish from Maine.

Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush)

Lake trout. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Lake Trout are native to the northern parts of North America, including the Finger Lakes. These large fish reach weights of 15-40 pounds and lengths greater than 3 feet. They prefer cold (44-55 °F), oxygen-rich, low-nutrient waters. Lake Trout are slow-growing fish, and very late to mature. This makes their populations extremely susceptible to overfishing. There was a commercial fishery for Lake Trout in Cayuga Lake in the 19th century.

Lake Trout reproduction in Cayuga Lake is poorly understood. It is the only trout in Cayuga Lake that does not spawn in streams. Some natural reproduction is observed, but it may not be enough to sustain the population. Reproductive failure may be caused by heavy silt levels in spawning areas, as well as thiamine deficiency from eating introduced Alewife (this is also the case with Atlantic Salmon; see above). The species has been stocked in Cayuga Lake since the 1930s.

Lake Trout is the most important sport fish in the Finger Lakes. Geneva, New York, at the north end of Seneca Lake, calls itself the “Lake Trout Capital of the World,” and holds an annual lake trout fishing derby.

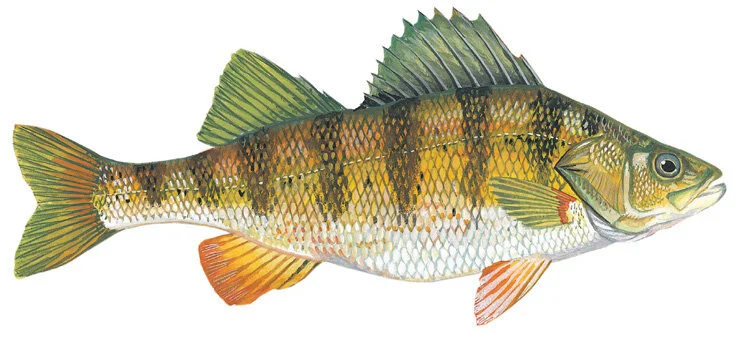

Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens)

Yellow perch. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Yellow Perch are shallow-water fish that move in large, loosely organized groups. They are mostly active during the day. They remain active during the winter, continuing to move and feed beneath the ice.

Spawning occurs in early spring, at night, over brush or vegetation. The young hatch in 7-10 days. Young feed first on zooplankton, switching to small insects and crustaceans before the end of the first year. Adults also feed on insects, but in addition eat crayfish and small fishes. Yellow perch live 8-9 years and reach 10-11 inches. They become mature at 3-4 years.

Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus)

Bluegill. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Bluegill originally ranged from the St. Lawrence River to Georgia, and west to Texas and Minnesota. They have been introduced well beyond this range, including throughout New York and across the U.S., as well as in Europe and South America.

Bluegill spawn in early summer, and nest in “colonies” in which each male creates a circular depression in the bottom in shallow water. The female is attracted to it and spawning occurs there. The male guards the nest and young until they disperse. The males are brightly colored at this time and defend the nest actively. Bluegill feed during the day, the young on zooplankton and larger fish on insects, aquatic invertebrates, and smaller fish. They may live for 10-11 years and reach 10 inches in length. Most individuals are 6-9 inches long.

Bluegill are very similar to Pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus), which also occur in Cayuga Lake. They are most easily distinguished by Pumpkinseed having a red spot on its opercular flap (the outer covering of the gills), whereas Bluegill have a blue-black spot.

Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu)

Smallmouth bass. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Smallmouth Bass are native to the upper and middle Mississippi River basin, the St. Lawrence River-Great Lakes system, and north into the Hudson Bay basin, a more northerly distribution than Largemouth Bass. Like Largemouths, however, Smallmouths have been widely introduced across the U.S. and Canada as a game fish.

Smallmouth Bass may be distinguished from Largemouths by several features including their bronze-brown coloration, their mottled pattern of dark bands, and their smaller mouth. Smallmouths are found in clearer and cooler waters than Largemouths, especially streams, rivers, and sandy and rocky bottoms of lakes and reservoirs. Because they are intolerant of pollution, Smallmouths are good natural indicators of a healthy aquatic environment.

These fish are common throughout the Finger Lakes region, where they typically reach 12-17 inches and 6-8 lbs. They are often found near shore and frequently feed on the bottom on crayfish. During late fall and winter, Smallmouth will often move to deeper water in which they enter a semi-hibernation state, moving sluggishly and feeding very little until the warm season returns.

In the U.S., Smallmouth Bass were first introduced outside of their native range with the construction of the Erie Canal in 1825, extending the fish's range into central New York state. During the mid-to-late 19th century, they were introduced throughout the northern and western U.S., as far as California. Smallmouth populations began to decline in many places after years of damage caused by overdevelopment and pollution. In recent years, improved water quality and stricter management practices have contributed to increased populations in many areas.

Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides)

Largemouth bass. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Largemouth Bass are large fish (up to 11 lb and 20 inches long) native to the eastern and central U.S., but widely introduced around the world.

Adults usually feed on small fish, including perch, sunfish, and minnows, but are also known to eat crayfish, insects, frogs, and even small aquatic birds and mammals. They have an excellent sense of smell, and can detect prey by following scent trails. Young under about two inches feed on zooplankton and insect larvae.

Adults are generally solitary, hiding among rocks, aquatic vegetation, or roots and limbs of sunken trees, striking at their prey from the shadows. During the day and early evening, largemouth bass are usually found in shallow water close to shore, and usually feed in early morning or late in the day. After dark, they move to deeper water, where they rest on the bottom under logs or trees. In cold temperate climates, largemouth bass generally move into deeper waters during the winter months and to warmer, shallow waters in the springtime.

Largemouth Bass spawn in the spring, beginning when they are about a year old. Males create nests in shallow water on bottoms composed of sand, gravel, or pebbles by moving debris using their tails. Shortly after spawning, the female departs and the male is left to guard the developing eggs until they hatch 3-7 days later. Female Largemouth Bass are usually larger than males of the same age. Females may reach a maximum age of 9 years, while males reach a maximum of 6 years.

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata)

American eel. Illustration by Duane Raver.

American Eel are the only catadromous species of freshwater fish in New York State, meaning that adults migrate out to sea to spawn. Spawning adults and eggs have never been found, and adults are thought to die after spawning. Eel larvae drift in the ocean for approximately one year before they enter coastal rivers and move upstream. When they reach about 2.5 inches, larval eels metamorphose into the classic eel shape. Eels can spend ten years in freshwater before returning to the sea to spawn.

The original taxonomic description of the American eel.

In freshwater, American Eel hunt mostly at night, hiding or remaining near the bottom during the day. They feed on crustaceans, aquatic insects, and other aquatic organisms. Adults can reach lengths of 4 feet and weights of 17 pounds.

The first described specimens of American Eel came from Cayuga and Seneca Lakes in 1817. Today, the species is rare in New York freshwaters, because dams and locks make it difficult for them to migrate to and from the ocean.

Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon marinus)

Sea lamprey. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Lampreys lack jaws and have skeletons made of cartilage. Sea Lamprey occur on both sides of the North Atlantic. Although commonly thought of as invasive, genetic evidence suggests that natural landlocked populations once occurred in the Great Lakes and the Finger Lakes. If not landlocked, Sea Lampreys spend their adult lives in the ocean, and then migrate into fresh water to spawn.

In Cayuga Lake, Sea Lamprey spawn in several tributaries, including Cayuga Inlet. After spawning, the adults die, but within a week the tiny larvae hatch and burrow into the bottom. They live as filter feeders for up to 5 years before metamorphosing into adults. Adults are parasitic, attaching to other fish with their sucker-like mouths and ingesting blood and other fluids from the prey. Sea Lampreys live 1-2 years, and can reach 4 feet in length.

Because of their parasitic habit, Sea Lampreys are often seen as a threat to sport fisheries. Attempts have been made to lower larval lamprey populations in Cayuga Lake and its tributaries. These efforts, including poisoning, have had mixed success.

Introduced Species in Cayuga Lake

Fish

Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens)

Lake sturgeon. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Lake Sturgeon are the largest (up to 5 feet long and 80 pounds) and longest-living (up to 150 years) freshwater fish in New York State. They are bottom-feeders, and belong to an ancient group of fishes with about 24 living species. All sturgeons have cartilaginous skeletons, and bony plates on their sides and backs. Almost all sturgeon species are currently at some risk of extinction.

Lake Sturgeon are native to most of northeastern North America. They were abundant in the Great Lakes and surrounding waters until the early 20th century, when overharvest and habitat degradation reduced their populations. The species was probably not present in Cayuga Lake before European arrival, because they could not easily pass the falls at Oswego, NY. The earliest published report of Lake Sturgeon in the Finger Lakes was in 1856. Before recent restocking, the last report was in 1961. Lake sturgeon have been stocked in Cayuga Lake since 1995, and were seen spawning in Fall Creek in Ithaca in 2017.

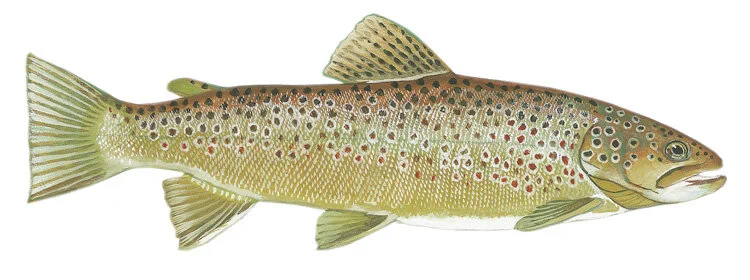

Brown Trout (Salmo trutta)

Brown trout. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Brown Trout are native to northwest Europe, but were introduced around the world during the 19th century. They were first introduced to New York State in 1883.

Like Rainbow Trout, Brown Trout include freshwater populations along with anadromous forms that breed in rivers but move to the sea for most of their life. In freshwater, they eat aquatic invertebrates, other fishes, frogs, mice, birds, and flying insects. They may live up to 20 years (usually 9-10 years), and reach weights of more than 20 pounds.

Brown Trout live in both lakes and streams, but they spawn almost exclusively in streams. In Cayuga Lake, the species is regularly stocked but also breeds in tributaries to the lake.

Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

Rainbow trout. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Rainbow Trout are native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in western North America and northeastern Asia. They were originally anadromous (breeding in rivers but moving to the sea for most of their life). They have been introduced into freshwater in at least 45 countries on every continent except Antarctica, and arrived in New York in 1874.

Rainbow Trout prefer water temperatures below 70°F. They live 6-7 years, and may reach 20-22 inches and 3-4 pounds. They are predators with a varied diet, including smaller fishes, fish eggs and larvae, insects, and crustaceans.

Rainbow Trout are stocked in Cayuga Lake, but Cayuga Inlet and Salmon Creek also have self-sustaining spawning runs.

Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus)

Alewife. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Alewives are small herring that are mostly anadromous. Early fish surveys of Cayuga Lake in the 1870s reported that Alewife were abundant, but before the construction of canals in the 19th century, waterfalls on the Oswego River prevented these fish from reaching the Finger Lakes.

Alewife are a favored prey for Cayuga Lake’s native apex predators, Lake Trout and Atlantic Salmon. Unfortunately, Alewife have high levels of an enzyme, thiaminase, that interferes with the predators’ reproduction. As a result, Lake Trout and Atlantic Salmon populations in Cayuga Lake are mainly sustained by stocking hatchery-reared fish.

Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus)

Round goby. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Round Goby are bottom-dwelling fish native to central and eastern Eurasia, including the Black and Caspian seas. In North America, Round Goby were first seen in 1990 near Detroit, Michigan. From there, they multiplied throughout the Great Lakes, reaching other inland waters. First reported in Cayuga Lake in August 2013, they soon became the lake’s dominant bottom-dwelling fish.

Round Goby are specialists that feed on mollusks (clams and snails) in their native European waters. They are particularly successful in waters colonized by zebra mussels, another European invader. Their fast growth and high fertility allows them to quickly displace native bottom-dwelling fishes.

Round Goby have significantly altered food webs in Cayuga Lake. As with other invasive species, populations of Round Goby will likely diminish at some point. For the foreseeable future, however, they will remain an important member of the Cayuga Lake fish community.

Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio)

Common carp. Illustration by Duane Raver.

This Asian species was first introduced into New York in 1831 as a food fish. Currently found in waters across the state, carp can grow very large; the state record is 50 pounds.

Mollusks

Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) and Quagga Mussels (Dreissena bugensis)

Zebra mussel. Illustration by Duane Raver.

Quick Overview

Zebra mussels were brought to the Great Lakes region from Europe in the ballast water of ocean-going ships. They were first reported in North America in 1988, and in Cayuga Lake in 1991. Today they are widely distributed throughout the lake, especially in near-shore areas. Zebra mussels can reach astonishing densities of up to hundreds of thousands per square foot.

Zebra mussels have changed freshwater ecosystems throughout North America. As efficient filter feeders, they increase water clarity, decrease plankton, and alter food webs. Zebra mussels compete with native mussels for resources, resulting in the loss of almost all native mussels from much of Cayuga Lake.

The arrival of Round Goby in the Finger Lakes and other areas inhabited by zebra mussels has changed these ecosystems yet again. Round Goby prey on zebra mussels in a relationship that evolved in their native Europe. Round Goby are now consuming large numbers of zebra mussels in the Finger Lakes. Over time, this could permanently lower the mussels’ numbers.

Biology and Taxonomy

Differences between zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) and quagga mussels (Dreissena bugensis). Image by Myriah Richerson (USGS; public domain).

Zebra mussels are small freshwater clams (bivalves). They get their name from a striped pattern usually present on their shells. They are usually about the size of a fingernail, but can reach nearly 2 in (5.1 cm). Their shells are roughly D-shaped, and attached to the substrate with strong threads called the byssus, which are produced by the animal’s foot and extend out of the shell on the hinged side. Quagga mussels (named after a now-extinct relative of zebras) are very similar to zebra mussels. Both species belong to the family Dreissenidae, and are therefore together frequently referred to as “dreissenids”.

Dreissenid mussels probably arrived in North America in the ballast water of ocean-going ships in 1985-86; the first reported zebra mussel in North America was collected on June 1, 1988 from Lake St. Clair, and a month later they were first seen in Lake Erie. The first quagga mussel, originally identified as a zebra mussel, was collected from Lake Erie in September 1989. It was later identified (genetically) as a separate species previously also known only from Europe.

Zebra and/or quagga mussels have now been detected in more than 1,000 natural or artificial lakes and more than 130 rivers in at least 26 states in the U.S. and the Canadian province of Ontario. They have changed the structure and function of freshwater ecosystems throughout North America and Europe. These mussels have many direct and indirect effects on streams and lakes, including changes to the food web, increased water clarity, and decreased abundance of plankton, which they filter out of the water.

Ecology and Environmental Impact

Zebra mussels with their siphons extended to filter feed. Image by “GerardM” (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

Dreissenids are filter-feeders and live by pumping water over their gills and eating the phytoplankton they strain out. Dreissenids are extremely efficient at this. One adult mussel can filter one quart of water per day. They also spread very quickly. This is due to the combination of their planktonic (free-floating) larvae, prolific reproduction (the mussels reach sexual maturity after 1-2 years, and one female can release up to one million eggs in a spawning season), and low predation (because most of the organisms that are natural enemies in Europe are not present in North America). They can reach extremely high densities (up to tens of thousands per square foot), and so their environmental impact can be enormous.

Zebra mussels growing on top of a Higgins eye pearly mussel, an endangered species. Photograph by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Public Domain).

The material that the mussels filter out but do not eat (called pseudofeces) are expelled and accumulate on the bottom. As these waste particles decompose, oxygen is used up, water acidity increases, and toxic byproducts are produced. Dreissenids can also accumulate pollutants within their tissues to levels much higher than concentrations in the environment; these pollutants are found in their pseudofeces, which can be passed up the food chain, therefore increasing wildlife exposure to organic pollutants. Because they reproduce and grow so quickly, dreissenids can overgrow and smother native freshwater mussels.

Dreissenids and People

Because they spread so quickly and cover all available hard substrate, dreissenids can pose serious challenges to various human activities. Water treatment plants, utilities, and other users withdrawing water from shallow depths (<33 feet) have found it necessary to employ control measures to minimize or prevent fouling by mussel colonization.

Dreissenids in Cayuga Lake

Zebra mussels exposed at low water, Stewart Park, Ithaca, NY.

Zebra mussels were first identified in Cayuga Lake in 1991 and in nearby Seneca Lake in 1992. They quickly became widely distributed throughout the lake, with dense populations noted in the shallower near-shore areas. Quagga mussels were first identified in Cayuga and Seneca lakes in 1994. Some evidence suggests that quagga mussels can live in deeper water and influence the ecological food web to a greater extent than the zebra mussels. Other studies suggest that quagga mussels may be replacing zebra mussels in several lakes in which zebra mussels were once dominant. It is likely that dreissenids have resulted in the loss of nearly all native mussels from the main body of Cayuga Lake.